Global rebalancing and recovery contributions

Global rebalancing and recovery contributions

After briefly shrinking during the global crisis, global imbalances in trade and financial flows have made a comeback during the recovery and remain large as of today. While the balances of the main surplus and deficit countries or regions are below their pre-crisis peak in both current dollar terms and as a per cent of World GDPgross domestic product, there has been no fundamental change in the global imbalance constellation. This is despite the fact that the global crisis also triggered prominent initiatives for establishing global policy coordination procedures focused on achieving a benign global rebalancing – as part of joint agenda for sustaining global recovery and avoiding a renewed build-up of imbalances.

In a globally integrated economy, international coordination of economic policies is essential. At their Pittsburgh Summit in September 2009, the G20 G20 The Group of Twenty is a forum for international cooperation between the world's major advanced and emerging economies (19 countries members plus the European Union) on the most important aspects of the international economic and financial agenda.

Leaders designated the Group as the premier forum for international economic cooperation. The G20 replaced the G8 in this role to better reflect the new realities in the world economy. G20 leaders agreed to launch a new Framework for Strong, Sustainable and Balance Growth as the centrepiece of economic policy coordination among members. Success critically hinges on a certain degree of commonality of policy views among members, which remains problematic. Furthermore, success also hinges on the adoption of policies that are suitable to sustain global recovery and foster rebalancing.

Since mid-2010, there has been a clear shift in the general policy orientation. While the previous position was that fiscal stimulus should be maintained until recovery was assured, fiscal consolidation became established as the new policy priority at that time; although clear policy rifts emerged on the matter, with Europe leading the rush to the exit and shifting towards unconditional continent-wide austerity. There are also conflicting policy views as to how global imbalances could be reduced. Disagreements pertain to which policy adjustments may be best suited for reducing excessive imbalances, and which countries should undertake most of those adjustments.

The extent to which particular economies or groups of economies have actually adjusted since the crisis is reflected in the composition of contributions to their respective GDP growth Contribution of a component (net exports, domestic demand etc.) to GDP growth is usually calculated as the real growth rate of this component weighted by the share of this component in the GDP in the previous period.

moreand their respective domestic demand contributions to global GDP growth. Broadly speaking, global rebalancing requires that surplus countries become less reliant on net exports and more reliant on domestic demand for their growth while deficit countries should do the opposite. The rebalancing process may be partly facilitated through adjustments in international competitiveness positions and partly through macroeconomic policies attuned to either boost or restrain domestic demand growth in particular countries or regions; the ideal mix of policies depending on the nature of imbalances existing at the outset.

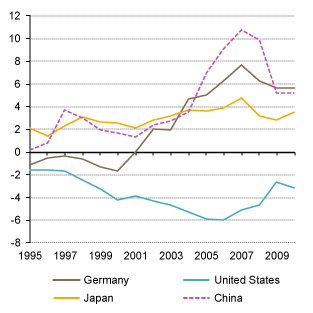

Current account, net, of Germany, the United States, Japan and China, 1995-2010

(Percentage of GDP)

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on UNCTADstat

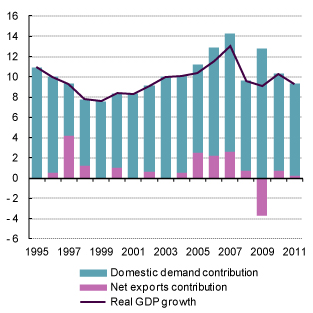

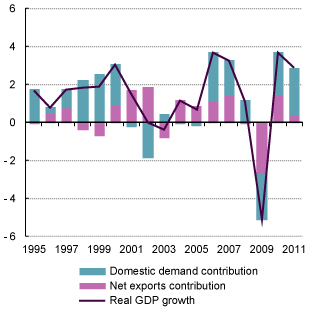

The most drastic adjustments have occurred in China. China’s GDP growth had been primarily domestic demand driven even prior to the global crisis, and net exports only made a significant positive contribution in the years 2005–2007 As the crisis struck, domestic demand growth was sustained by means of a large stimulus programme, whereas the growth contribution of net exports has turned negative in the meantime (Chart) Real gross domestic product growth and contribution of net exports and domestic demand in China, 1995-2011

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2010 (Chart 1.4), March 2012 update; National Bureau of Statistics of China, Statistical Yearbook 2010 and The World Bank, China quarterly, April 2011 update . Expressed as a share of national GDP, China’s current account surplus has declined sharply from its peak of over 10 per cent to 2–3 per cent in 2011. The adjustment has involved a gradual, managed appreciation of the renminbi’s REERreal effective exchange rate.

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2010 (Chart 1.4), March 2012 update; National Bureau of Statistics of China, Statistical Yearbook 2010 and The World Bank, China quarterly, April 2011 update . Expressed as a share of national GDP, China’s current account surplus has declined sharply from its peak of over 10 per cent to 2–3 per cent in 2011. The adjustment has involved a gradual, managed appreciation of the renminbi’s REERreal effective exchange rate.

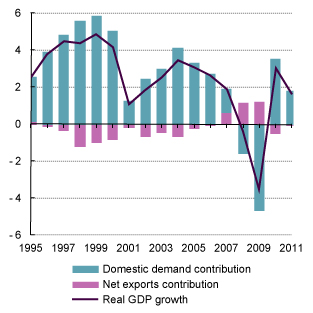

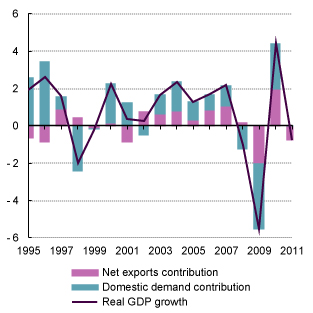

Drastic changes also characterize the situation in the United States. Sizeable negative growth contributions by net exports characterizing the pre-global crisis era have disappeared. While recovery is driven entirely by domestic demand, budget deficits and public debt have replaced earlier private deficit spending and private debts as drivers of domestic demand growth (Chart) Real gross domestic product growth and contribution of net exports and domestic demand in the United States, 1995-2011

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2010 (Chart 1.4), March 2012 update . The United States dollar’s REER has moved downwards since the global crisis, as appropriate. The challenge remains to ensure fiscal consolidation by means of sustained recovery. Austerity can only fail to reach that end, as the European example clearly shows.

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2010 (Chart 1.4), March 2012 update . The United States dollar’s REER has moved downwards since the global crisis, as appropriate. The challenge remains to ensure fiscal consolidation by means of sustained recovery. Austerity can only fail to reach that end, as the European example clearly shows.

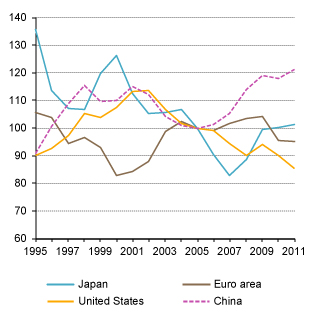

Real effective exchange rate of euro area, the United States, Japan and China, 1995-2011

(Index numbers, 2005=100, CPI based)

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on BIS, Broad indices

Note: The weights are based on trade data in 2008-2010.

Among European countries, Germany’s GDP growth was spectacularly unbalanced prior to the global crisis, almost exclusively reliant on net exports for the country’s meagre growth. After having suffered severely from the trade collapse, Germany again benefited handsomely from trade for its recovery. While net exports again provided outsized positive growth contributions in 2010–2011, domestic demand too revived and contributed somewhat more than prior to the crisis (Chart) Real gross domestic product growth and contribution of net exports and domestic demand in Germany, 1995-2011

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2010 (Chart 1.4), March 2012 update . Owing to stresses inside the euro area, Germany’s REER has moved contrary to what is needed for global rebalancing. With the recovery derailed by unconditional continent-wide austerity, the European Union faces a double-dip recession in 2012 and a highly uncertain economic outlook beyond that year. The world’s foremost trader is becoming a rising drag on global GDP growth and poses the foremost threat to sustained recovery.

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2010 (Chart 1.4), March 2012 update . Owing to stresses inside the euro area, Germany’s REER has moved contrary to what is needed for global rebalancing. With the recovery derailed by unconditional continent-wide austerity, the European Union faces a double-dip recession in 2012 and a highly uncertain economic outlook beyond that year. The world’s foremost trader is becoming a rising drag on global GDP growth and poses the foremost threat to sustained recovery.

The picture in Japan was very similar to Germany’s prior to the crisis: notorious reliance on net exports for growth(Chart)Real gross domestic product growth and contribution of net exports and domestic demand in Japan, 1995-2011

(Percentage) Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2010 (Chart 1.4), March 2012 update; and OECD, StatExtracts, Quarterly National Accounts dataset. The unwinding of the yen carry trade has partly corrected the yen’s misaligned REER since the global crisis. Tragic natural disasters unravelled domestic demand in 2011.

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2010 (Chart 1.4), March 2012 update; and OECD, StatExtracts, Quarterly National Accounts dataset. The unwinding of the yen carry trade has partly corrected the yen’s misaligned REER since the global crisis. Tragic natural disasters unravelled domestic demand in 2011.

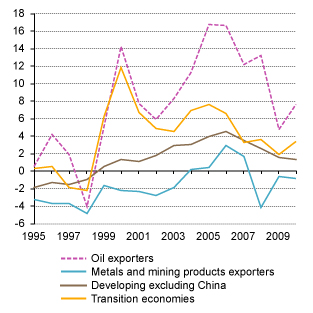

The commodity exporters group’s aggregate current account balance has turned from a pre-global crisis surplus position into a growing deficit during the recovery. The growth rebound in these economies was domestic demand driven, with net exports making negative growth contributions. As private capital flows have in some cases pushed up currencies very significantly, current account deficits (Chart) Current account, net, of selected groups, 1995-2010

(Percentage of GDP) Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on UNCTADstathave grown large in a growing number of developing countries, posing future risks of fragility and crisis.

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on UNCTADstathave grown large in a growing number of developing countries, posing future risks of fragility and crisis.

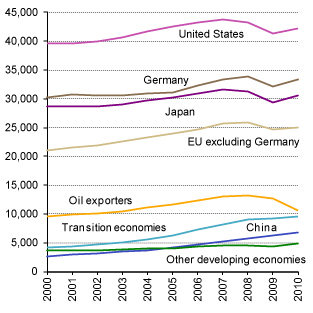

In conclusion, any notion that developing countries at large, and China in particular, may be assisting the global rebalancing effort insufficiently seems untenable. Strong domestic demand growth in developing countries has made outsized contributions to world gross product growth in recent years. These developments once again highlight the shifting balance in the world economy that was accelerated by the global crisis (Chart) Level of gross domestic product per capita in terms of purchasing power parity in selected economies, 2000-2010

(Constant 2005 international $)  Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on World Bank, World Databank; and OECD, OECD.Stat Extracts Note: 'Other developing economies' comprise all developing economies excluding China and oil exporters. .

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on World Bank, World Databank; and OECD, OECD.Stat Extracts Note: 'Other developing economies' comprise all developing economies excluding China and oil exporters. .

Highlights

- After briefly shrinking during the global crisis, global imbalances in trade and financial flows have made a comeback during the recovery and remain large;

- While the balances of the main surplus and deficit countries or regions are below their pre-crisis peak, there has been no fundamental change in the global constellation;

- Developing countries at large, and China in particular, have experienced a significant rebalancing of their growth towards domestic demand;

- Among developed countries, recovery in the United States is exclusively carried by domestic demand, while Japan and Germany remain primarily export-reliant economies;

- Derailed by unconditional continent-wide austerity, the European Union represents the foremost threat to global rebalancing and sustained recovery.

To learn more

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2011, Chapter I Current Trends and Issues in the World Economy, UNCTAD/TDR/2011

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2010, Chapter I After the Global Crisis: an Uneven and Fragile Recovery, UNCTAD/TDR/2010

South-South Integration is Key to Rebalancing the Global Economy, UNCTAD Policy Briefs, No. 22, 22/02/2011