Current account imbalances

Current account imbalances

Countries running a current account Current account includes all the transactions recorded in the balance of payments (other than those in financial items) that involve economic values and occur between resident and non- residents entities. Specifically, the major classifications are: goods and services; income and current transfers.

surplus must by necessity either experience net private capital outflows Private capital flows cover direct investment, portfolio investment and other investment.

or accumulate international reserves Reserves consist of those external assets that are readily available to and controlled by a country's authorities for direct financing of international payments imbalances, for indirect regulation of the magnitude of such imbalances through intervention in foreign exchange markets to affect their currency's exchange rate, and for other purposes.

more(i.e. official outflows). Similarly, countries running a current account deficit must by necessity either experience net financial inflows or run down its international reserve holdings. The United States provides a special case because the United States dollar serves as the world’s key reserve currency. The large and persistent United States current account deficits since the 1990s did not involve any run-down of the country’s international reserves. Rather, the equally large net capital inflows into the United States were partly net private inflows and partly official inflows, the latter being other countries’ accumulation of international reserves held in United States dollar assets.

When global imbalances and large United States current account deficits first emerged in the 1980s, the main surplus countries or regions were Japan and Western Europe – mainly Germany – also reflecting the fact that the rich industrialized countries represented more than 70 per cent of global trade at the time. In the first half of the decade, the United States recovered more strongly from the second oil price shock and the dollar appreciated strongly. The United States current account deficit then briefly disappeared by 1990 as the dollar depreciated strongly after the Plaza Accord of 1985, and GDP gross domestic product growth in Japan and Western Europe picked up in the second half of the decade.

The (re-) emergence of rising and persistent United States current account deficits since 1991 at first featured mainly the same surplus countries or regions as their counterpart. In both Japan and the European countries preparing to adopt the euro as their currency GDP growth was very sluggish during much of the 1990s while the United States dollar experienced a sizeable appreciation over the course of the decade. Imbalances among these developed countries or regions continued or increased until the global crisis. Apart from Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland feature prominently among rich European countries with sizeable, persistent surpluses.

| Current account, net, by region, 1980-2010 (Percentage of GDP) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | 1980 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | ||||||

| Developing economies | 1.2 | 0.4 | -1.6 | 1.4 | 4.6 | 2.4 | ||||||

| Africa | 1.5 | 0.7 | -2.7 | 2.8 | 6.1 | 0.4 | ||||||

| America | -4.1 | -0.4 | -2.1 | -2.3 | 1.3 | -1.1 | ||||||

| Asia | 4.2 | 0.6 | -1.2 | 3.1 | 5.6 | 3.9 | ||||||

| LDCs | -6.0 | -4.0 | -4.2 | -2.5 | -2.5 | -4.3 | ||||||

| Transition economies | -3.2 | -2.8 | 0.3 | 11.8 | 7.6 | 3.4 | ||||||

| Developed economies | -1.0 | -0.6 | 0.1 | -1.3 | -1.5 | -0.6 | ||||||

| Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on UNCTADstat | ||||||||||||

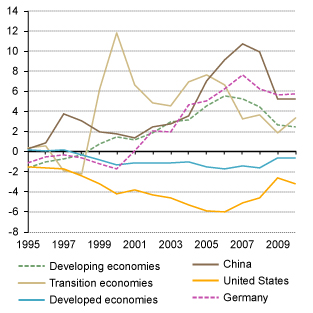

The global constellation became more complex at the end of the 1990s. In reaction to emerging market crises in East Asia in the late 1990s and Latin America in the early 2000s, many developing countries started running current account surpluses; with Eastern Europe as the exception. Mirroring a marked increase in the United States deficit, in the aggregate, the developing world’s deficit shifted into surplus. Capital exports from developing countries contradict traditional development theory, which predicts that capital should flow from rich to poor countries. While a sizeable Sino-American trade imbalance had built up earlier in the 1990s, China only emerged as a significant contributor to global imbalances in 2003. The commodity price boom of the 2000s then added fuel-exporting economies to the list of surplus countries (Chart) Current account, net, of selected economies, 1995-2009

(Percentage of GDP)  Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on UNCTADstat .

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on UNCTADstat .

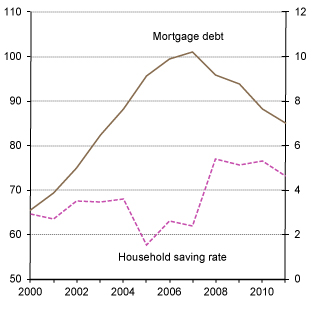

All along, the United States offset the deflationary forces originating in much of the rest of the world through widespread export orientation by encouraging borrowing and spending, particularly by private households. The resulting internal imbalances in the United States household and financial sectors began to implode as the property bubble burst in 2006 (Chart) United States mortgage debt and household saving rate, 2000-2011

(Percentage of disposable income)  Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal Reserve Economic Data and OECD, OECD.Stat Extracts (Chart) United States property price and current account, net, 2000-2011

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal Reserve Economic Data and OECD, OECD.Stat Extracts (Chart) United States property price and current account, net, 2000-2011

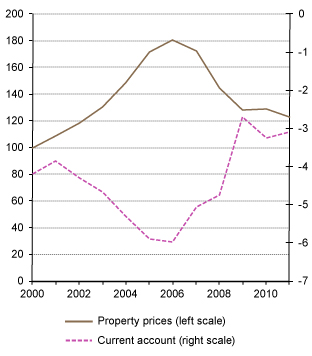

(Index numbers, 2000=100 and percentage of GDP)  Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on IMF, World Economic Outlook Database and Standard & Poor's, S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices .

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on IMF, World Economic Outlook Database and Standard & Poor's, S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices .

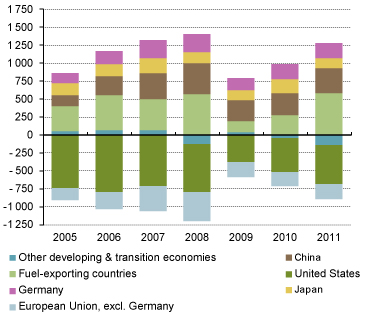

Current account balance of selected economies, 2005–2011

($ billions)

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on UN DESA, National Accounts Main Aggregates database, WESP 2011: Mid-year update; and IMF, WEO database

In current dollar terms, global current account imbalances peaked in 2007–2008, shrank in 2009 – when the volume and value of global trade declined sharply – and widened again in 2010–2011. The plunge and renewed surge in commodity prices – especially of oil – was a major factor in this. While the balances of the main surplus and deficit countries or regions are below their pre-crisis peak in both current dollar terms and as a per cent of world GDP, there has been no fundamental change in the imbalance constellation.

Current account imbalances may arise for a number of reasons. Sharp commodity price swings, as witnessed over the last decade, provide one prominent reason, as the spending adjustment in exporting and importing countries typically lags behind changing export revenues or import bills, respectively. Another reason may be that a country begins to serve as a major hub for foreign firms in producing manufactures on a large scale while its population may still lack the earning capacity to consume imports on a scale sufficient to balance out its surging exports (e.g. China). A third reason may arise when a country suffers from protracted domestic demand stagnation and comes to rely on exports for its growth (e.g. Japan and Germany). Finally, current account imbalances may result from the loss of competitiveness at the national level. While international tensions may arise for any of these reasons, current account imbalances per se are not indicative of a systemic problem that needs coordinated intervention. This would be the case, however, in the two last cases, in which changes in domestic demand and in real exchange rates may be needed. Through international cooperation, these changes may be achieved without incurring in a deflationary bias: Surplus countries should expand their domestic demand and cooperate in a smooth adjustment of real exchange rates.

Highlights

- Persistent and large current account imbalances built up prior to the global crisis;

- Imbalances are concentrated in a small group of countries;

- The United States, the world’s key reserve currency issuer, is the largest deficit country;

- Initially other developed countries were the main surplus countries;

- Developing countries joined this group in the late 1990s, with China appearing as a globally significant contributor only since 2003;

- Capital exports from developing countries contradict orthodox development theory;

- While the balances of the main surplus and deficit countries or regions are below their pre-crisis peak, there has been no fundamental change in the imbalance constellation;

- Current account imbalances may arise for a number of reasons;

- Current account imbalances caused by insufficient domestic demand in surplus countries and a loss of competitiveness in deficit countries require international coordination for a pro-growth rebalancing.

To learn more

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2011, Chapter I Current Trends and Issues in the World Economy, UNCTAD/TDR/2011

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2008, Chapter III International Capital Flows, Current-account Balances and Development Finance, UNCTAD/TDR/2008

Building a global monetary system: the door opens for new ideas, UNCTAD Policy Briefs, No. 17, 17/11/2010