Misaligned exchange rates

Misaligned exchange rates

The evolution of competitiveness Competitiveness is a measure of a country's advantage or disadvantage in selling its products in international markets.

moreat the national level is mainly shaped by two factors: first, the rate of increase in wages (and other costs) relative to the rate of productivity growth and, second, the nominal exchange rateNominal exchanges rate is the price of one currency in terms of another.

. While wage increases per se raise production costs and reduce competitiveness, productivity growth has the opposite effect. If both wages and productivity grow at the same rate, unit-labour costs stay steady; and so would external competitiveness assuming that profit margins, indirect taxes and other related factors remain unchanged too. Exchange rate changes broadly affect the competitiveness of all producers of tradable goods and services in a country relative to producers in trading partners by changing the foreign currency price of home exports and domestic currency price of foreign imports.

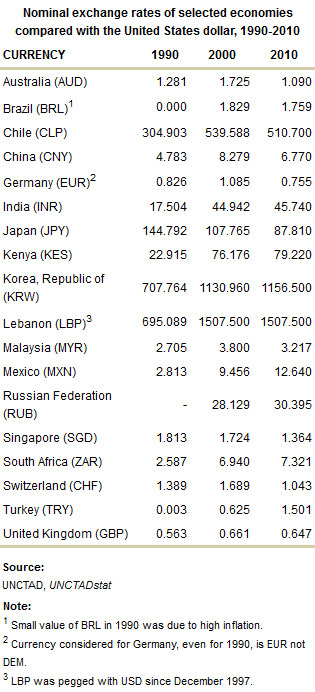

Since the breakdown of the multilateral Bretton Woods system of pegged but adjustable exchange rates in the early 1970s, currencies have entered a new era of non-orderly floating exchange rates, leaving it at countries’ discretion to choose their particular exchange rate regime. Members of today’s European Union established a new regional system of pegged but adjustable exchange rates, and at the end of the 1990s, some of them permanently fixed their exchange rates and adopted the euro as their common currency. Among developing countries, too, many have chosen to peg their currencies to or stabilize them against some anchor currencies, most prominently the United States dollar, at least during some of the time (Table)  .

.

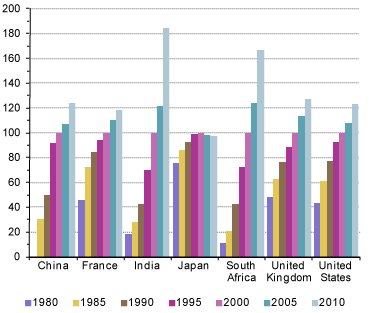

Trends of consumer price index in selected economies, 1980-2010

(Index numbers, 2000=100)

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on ILO, LABORSTA; OECD, OECD.Stat Extracts; IMF, IFS; and national sources

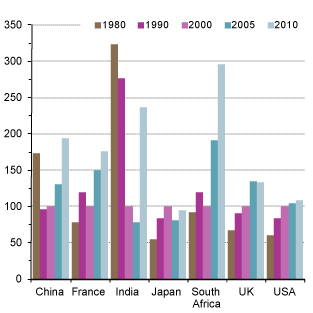

Movements in nominal exchange rates may not properly reflect corresponding changes in countries' competitiveness positions, which are also affected by inflation differentials. Except for changes in profit margins and indirect taxes, for example, inflation differentials in turn are mainly driven by trends in relative unit labour costs. Inflation differentials and divergent trends in unit-labour costs have been sizeable since the 1970s (Chart) Trends of nominal unit labour cost in selected economies, 1980-2010

(Index numbers, 2000=100)  Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on OECD, OECD.Stat Extracts and Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) online database .

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on OECD, OECD.Stat Extracts and Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) online database .

Correcting movements in nominal exchange rates for inflation differentials yields real exchange rates, which are more accurate indicators of changes in competitiveness. A still superior indicator of the overall competitiveness of a country relies on measures of real effective exchange rates Real effective exchange rates (REERs) take account of price level differences between trading partners.

more(REER). The term "effective" means that exchange rate changes are not measured against one particular currency, but instead use an average index of a whole basket of currencies, each weighted according to the issuing countries' respective importance as a trade partner.

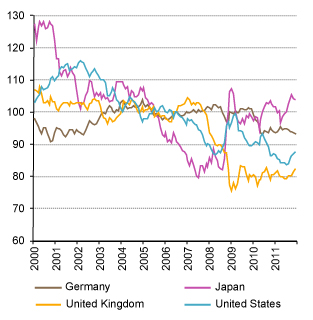

According to the REER measure, substantial changes in competitiveness positions have occurred since 2000. In principle, if the emergence of unsustainable current account imbalances is to be avoided and benign rebalancing the aim, countries with deficit positions should see their external competitiveness improve – and vice versa. Since 2007, there has been a sizeable depreciation in the REER of two large current account deficit countries, the United Kingdom and the United States, which seems to be in line with rebalancing requirements. The same holds for the marked rise in China’s REER since 2005. By contrast, significant improvement in Japan’s competitiveness up to 2008, even accelerating in the years 2005–2007, was inconsistent with the country’s surplus position. Equally inconsistent with rebalancing requirements, Germany has been awarded a significant improvement in competitiveness in the context of the European crisis. The fact that the euro area’s current account position is nearly balanced does not suggest otherwise, but implies that competitiveness positions inside the currency area may be seriously out of kilter (Chart) Real effective exchange rates of selected developed economies, January 2000-December 2011

(Index numbers, 2005=100, CPI based)  Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on BIS, Effective Exchange Rate Indices database .

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on BIS, Effective Exchange Rate Indices database .

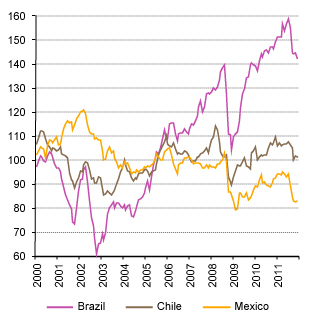

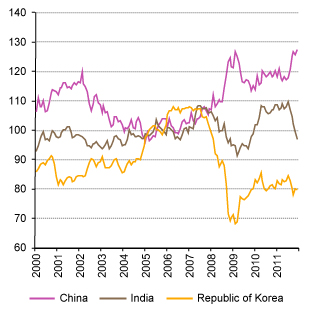

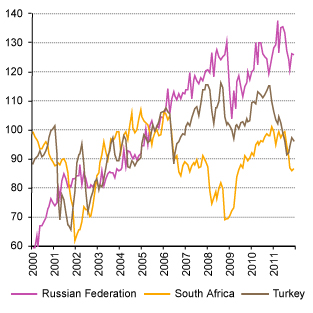

Real effective exchange rates of selected developing economies, January 2000-December 2011

(Index numbers, 2005=100, CPI based)

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on BIS, Effective Exchange Rate Indices database

Developing countries have often experienced even greater swings in competitiveness over the last decade. For instance, Brazil’s REER rose strongly until mid-2008, plunged at the peak of the crisis, only to resume its rise to new heights until mid-2011, when a new reversal started. Similar exchange rate trends have been observed in other developing countries, a number of which have meanwhile drifted into sizeable current account deficit positions which may herald future instabilities. The currencies of Chile, Mexico, India, the Republic of Korea (Chart) Real effective exchange rates of selected developing economies, January 2000-December 2011

(Index numbers, 2005=100, CPI based)  Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on BIS, Effective Exchange Rate Indices database , the Russian Federation, South Africa and Turkey (Chart) Real effective exchange rates of selected developing and transition economies,

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on BIS, Effective Exchange Rate Indices database , the Russian Federation, South Africa and Turkey (Chart) Real effective exchange rates of selected developing and transition economies,

January 2000-December 2011

(Index numbers, 2005=100, CPI based)  Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on BIS, Effective Exchange Rate Indices database , for example, underwent a significant appreciation in their REER following the recovery from the crisis; until renewed stresses arose in mid 2011.

Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations, based on BIS, Effective Exchange Rate Indices database , for example, underwent a significant appreciation in their REER following the recovery from the crisis; until renewed stresses arose in mid 2011.

Renewed instabilities are mainly related to the European crisis. The euro area provides a special case in which competitiveness positions among members can no longer change owing to exchange rate changes; trends in relative unit-labour costs determine competitiveness positions inside a currency union. To avoid dislocations in intraregional competitiveness positions, national wage trends need to follow an implicit norm that is the sum of national productivity growth and the agreed union-wide inflation rate (defined by the European Central Bank as “below but close to 2 per cent”).

Countries in the periphery that are experiencing severe public-debt crises today departed from this norm somewhat in the upward direction, whereas Germany, the economy with the largest trade surplus within the euro area, missed the implicit norm most widely, but in a downward direction. As a result, over time Germany experienced cumulative competitiveness gains over its European partners. Widening current account imbalances inside the euro area by necessity also had their financial counterparts. In some cases, lending flows towards current account deficit countries caused property bubbles. The bursting of those bubbles in the context of the global crisis resulted in private debt overhands that first triggered banking crises and eventually turned into sovereign debt crises. The build-up of unsustainable current account positions fosters financial fragilities that tend to end in tears, whether at the global or regional level, whether in the developing or developed world.

In conclusion, misaligned exchange rates affect competitiveness positions and cause current account imbalances, which matter both at the regional and global levels. Inside currency unions, relative trends in unit-labour costs are the key. In general, exchange rate movements that are persistently inconsistent with achieving balanced global competitiveness positions provide strong evidence for the need to coordinate global currency markets.

Highlights

- Countries’ competitiveness positions are shaped by trends in unit-labour costs and exchange rates;

- Since the end of the multilateral Bretton Woods exchange rate system, non-orderly floating has prevailed, featuring large exchange rate swings and persistent misalignments;

- Current account imbalances caused by unbalanced competitiveness positions matter both at the regional and global levels;

- Exchange rate movements that are persistently inconsistent with achieving balanced global competitiveness positions provide strong evidence for the need to coordinate global currency markets.

To learn more

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2011, Chapter VI The Global Monetary Order and the International Trading System, UNCTAD/TDR/2011

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2009, Chapter IV Reform of the international monetary and financial system, UNCTAD/TDR/2009

Global imbalances: The choice of the exchange rate-indicator is key, UNCTAD Policy Briefs, No. 19, 12/01/2011

Will we never learn? UNCTAD Policy Briefs, No. 5, 18/12/2008