Employment and unemployment

Employment and unemployment

Work represents – for the majority of the population – the main source of personal income, the other sources being the revenues from capital and social transfers. For working-age populations, employment Employment should include full- and part-time employees on the payroll, but not contract and temporary employees. Ideally, figures for part-time employees should be reported on a full-time equivalent basis.

is also essential for social inclusion. As productivity growth and structural change, featuring job destruction, are inherent aspects of development, the timely creation of jobs in sufficient numbers is a permanent challenge. Job creation is of even more vital importance when population growth in conjunction with demographic and social factors yield a growing labour force ready for employment – or at risk of raising the reserve of unemployed or underemployed workers. Widespread unemployment Unemployment exits when a person above a specified age who during the reference period were without work, that is, were not in paid employment or self employment; currently available for work; and seeking work, that is, had taken specific steps in a specified recent period to seek paid employment or self-employment.

moreand underemployment Underemployment exists when a person's employment is inadequate in relation to specified norms of alternative employment, account being taken of his or her occupational skill.

in the global economy continues to present the most pressing social and economic problem of our time because it is closely related to poverty, on the one hand, and social peace and political stability on the other.

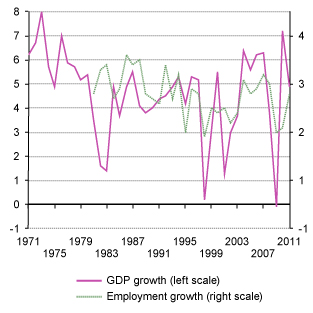

Growth of employment and real gross domestic product in developed economies, 1971–2011

(Percentage)

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1) and TDR 2010 (Chart 3.3) March 2012 update; UNCTADstat database and Historical Statistics of Japan, Statistical Bureau

Note: Developed countries comprise: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

In developed economies, there is a strong link between GDP gross domestic product growth and employment creation. By contrast, in developing economies, changes in informal employment and self-employment dampen the effects of growth cycles on formal employment (Chart) Growth of employment and real gross domestic product in developing economies, 1971–2011

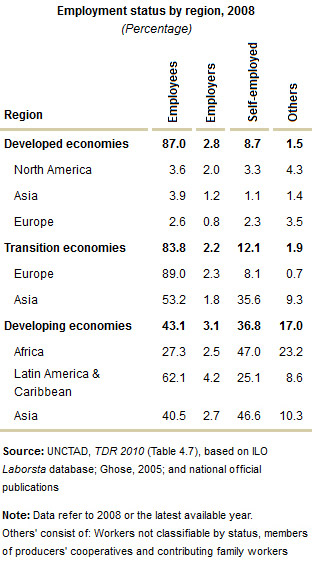

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1) and TDR 2010 (Chart 3.3) March 2012 update; and UNCTADstat database Note: Developing economies comprise: Argentina, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, China, Hong Kong (SAR), China, Taiwan Province of, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Malaysia, Mauritius, Mexico, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda and Uruguay. . In the absence of social safety nets fulfilling this role in developed economies, in developing economies movements into and out of informal, low-quality employment is typically cushioning employment in the formal economy as captured in official statistics, if at all. The segmentation of the labour structure in developing countries reflects the dualism that characterizes their economic structures: The coexistence of a modern sector with relatively high productivity and a sluggish traditional sector with low productivity. Moreover, the segmentation also highlights the importance of the quality of employment created; above and beyond the sheer quantity of, perhaps, precarious and poorly paid jobs feeding the ranks of the working poor. While unemployment rates always have to be assessed in conjunction with labour force and employment data in both developed and developing countries. Classification of workers by employment status underlines that the self-employed and contributing family members continue to play a far more prominent role in developing countries (Table)

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1) and TDR 2010 (Chart 3.3) March 2012 update; and UNCTADstat database Note: Developing economies comprise: Argentina, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, China, Hong Kong (SAR), China, Taiwan Province of, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Malaysia, Mauritius, Mexico, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda and Uruguay. . In the absence of social safety nets fulfilling this role in developed economies, in developing economies movements into and out of informal, low-quality employment is typically cushioning employment in the formal economy as captured in official statistics, if at all. The segmentation of the labour structure in developing countries reflects the dualism that characterizes their economic structures: The coexistence of a modern sector with relatively high productivity and a sluggish traditional sector with low productivity. Moreover, the segmentation also highlights the importance of the quality of employment created; above and beyond the sheer quantity of, perhaps, precarious and poorly paid jobs feeding the ranks of the working poor. While unemployment rates always have to be assessed in conjunction with labour force and employment data in both developed and developing countries. Classification of workers by employment status underlines that the self-employed and contributing family members continue to play a far more prominent role in developing countries (Table)  .

.

| Real gross domestic product and employment by region, 2003–2011 (Annual average growth rate) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | 03-08 | 09-10 | 2011 | |||||||||

| Developing economies | 7.0 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 1.4 | 6.0 | .. | ||||||

| East Asia | 8.9 | 0.6 | 8.6 | 0.4 | 7.6 | 2.0 | ||||||

| South Asia | 8.0 | 2.5 | 7.5 | 1.4 | 6.5 | 2.2 | ||||||

| South-East Asia | 6.0 | 2.0 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 4.8 | 2.7 | ||||||

| West Asia | 6.3 | 2.3 | 5.2 | 3.6 | 6.6 | 4.3 | ||||||

| North Africa a | 5.1 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 2.3 | -0.5 | 1.3 | ||||||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 6.4 | 3.0 | 5.4 | 2.8 | 4.7 | .. | ||||||

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 4.8 | 2.8 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 4.3 | 1.9 | ||||||

| Transition economies | 7.4 | 1.2 | 5.4 | -0.5 | 4.5 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Developed economies | 2.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | -2.4 | 1.4 | 2.4 | ||||||

| North America | 2.4 | 1.3 | 1.5 | -2.0 | 1.7 | 0.7 | ||||||

| Asia | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.8 | -0.8 | -0.7 | -2.1 | ||||||

| Europe | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1.5 | -1.0 | 1.6 | 0.2 | ||||||

| Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1) and TDR 2010 (Chart 3.3), March 2012 update | ||||||||||||

| Note: a North Africa excluding Sudan. | ||||||||||||

Given the pivotal importance of GDP growth as contributing force behind job creation and the prevalence of unemployment or underemployment in economies in general, events such as the collapse in GDP growth in the global crisis are bound to have a major impact on the employment and labour market situation too. It turns out that countries that achieved a quick and full recovery from the crisis generally only experienced a temporary deterioration in the employment and labour market situation. Until now, this has proved true for developing countries at large, although regional disparities exist. The global crisis has temporarily dented the favourable trends established during the global boom of 2003–2007, but not derailed the benign developments. In principle, developing countries are thus generally facing the same kinds of challenges regarding job creation and poverty reduction as prior to the crisis, their principal problem being that of deficient productive capacity rather than its underutilization.

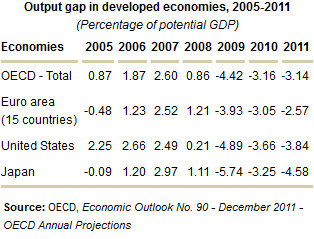

The situation is starkly different in major developed economies, where actual GDP is falling well short of potential output and large negative output gaps Output gap refers to the difference between actual and potential gross domestic product (GDP) as a per cent of potential GDP.

persist (Table)  . In these economies the short-run challenge remains to fully undo the crisis impact on GDP and employment by appropriate macroeconomic policies. In case of failure, crisis-induced unemployment would in due course be classified as structural, which would become true to the extent that a deterioration of human capital (a loss of skills and morale due to long-term unemployment) and lack of physical capital (for lack of investment) artificially creates a state of deficient productive capacity resembling the situation in developing countries. Labour market and welfare system reforms designed to accentuate downward wage pressures would not solve the underlying problem of deficiency of effective demand in these countries, but make them also more similar to developing countries in terms of a widespread prevalence of working poor. It would also tend to make these economies more export reliant and focused on external competitiveness.

. In these economies the short-run challenge remains to fully undo the crisis impact on GDP and employment by appropriate macroeconomic policies. In case of failure, crisis-induced unemployment would in due course be classified as structural, which would become true to the extent that a deterioration of human capital (a loss of skills and morale due to long-term unemployment) and lack of physical capital (for lack of investment) artificially creates a state of deficient productive capacity resembling the situation in developing countries. Labour market and welfare system reforms designed to accentuate downward wage pressures would not solve the underlying problem of deficiency of effective demand in these countries, but make them also more similar to developing countries in terms of a widespread prevalence of working poor. It would also tend to make these economies more export reliant and focused on external competitiveness.

The fragile and unfinished recovery of major developed economies affects developing economies as the former represent critical export markets for the latter. Ill-guided policies in developed countries pose new and additional challenges in developing countries.

Highlights

- There is a strong link between GDP growth and employment creation;

- The relative role of social safety nets and informal employment varies in developed vs. developing economies, and stark differences in employment status of the labour force persist;

- The employment impact of the global crisis has proved temporary in many developing economies, but lasting in major developed economies;

- The underlying problem of insufficient effective demand and possible ill-guided policies pursued in developed economies cause spillover effects in the developing world.

To learn more

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2010, Chapter II Potential Employment Effects of a Global Rebalancing, UNCTAD/TDR/2010

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2010, Chapter III Macroeconomic Aspects of Job Creation and Unemployment, UNCTAD/TDR/2010

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2010, Chapter IV Structural Change and Employment Creation in Developing Countries, UNCTAD/TDR/2010

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2010, Chapter V Revising the Policy Framework for Sustained Growth, Employment Creation and Poverty Reduction, UNCTAD/TDR/2010

Employment Dimension of Trade Liberalization with China: Analysis of the Case of Indonesia with Dynamic Social Accounting Matrix, UNCTAD/DITC/TNCD/2011/4

Trade and Employment: From Myths to Facts, International Labour Office, ISBN: 978-92-2-125320-4

Development Challenges Facing LDCs in the Coming Decade, UNCTAD Policy Briefs, No. 20(f), 10/05/2011