Incomes policy

The instruments available to policymakers for supporting economic recovery seem to have been limited after the crisis, especially in developed economies. On the one hand, there is little scope for monetary policy to provide additional stimulus, as interest rates has remained at historic lows, and quantitative easing has become more difficult to defend politically. Further, the ongoing deleveraging process associated to falling asset prices, made it extremely hard to revive credit to boost domestic demand. On the other hand, higher public-debt-to-GDP gross domestic product ratios have convinced many governments that they should shift to fiscal tightening.

While there is more space for proactive fiscal policies than what is perceived by policymakers, in addition, there are other policy tools, such as incomes Total income refers to regular receipts by individuals and/or household,s such as wages and salaries, income from self-employment, interest and dividends from invested funds, pensions or other benefits from social insurance and other current transfers receivable.

policy, that have been largely overlooked. These could play a strategic role in dealing with the present challenges.

In the period of intensified globalization from the early 1980s until the global crisis, the share of national income accruing to labour declined in most developed and developing countries. If real wage Wages and salaries are defined as "the total remuneration, in cash or in kind, payable to all persons counted on the payroll (including home workers), in return for work done during the accounting period" regardless of whether it is paid on the basis of working time, output or piecework and whether it is paid regularly or not.

growth fails to keep pace with productivity growth, there is a lasting and insurmountable constraint on the expansion of domestic demand and employment creation. To offset insufficient domestic demand, one kind of national response has been an overreliance on external demand. Another kind of response has taken the form of compensatory stimulation of domestic demand through credit easing and increasing asset prices. However, neither of these responses offers sustainable outcomes. These are important lessons to be learned from the global crisis.

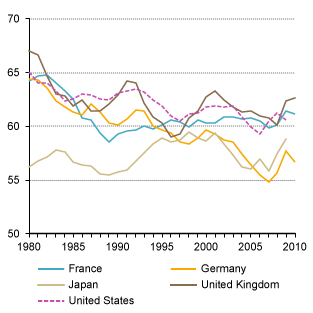

Share of wages in national income in selected developed economies, 1980-2010

(Percentage)

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Chart 1.5), based on OECD, Main Economic Indicators database; and Lindenboim, Kennedy and Graña, 2011

Trends in income distribution since the 1980s confirm that inequalities within many developed economies have increased as globalization has accelerated. In particular, wage shares have declined slowly, but steadily over the past 30 years, with short reversals during periods of recession – particularly in 2008–2009 – when profits tend to fall more than wages. After such episodes, however, the declining trend has resumed. This trend is creating hazardous headwinds in the current recovery. As wages have decoupled from productivity growth, wage earners can no longer afford to purchase the growing output, and the resultant stagnating domestic demand is causing further downward pressure on prices and wages, thus threatening to bring about a deflationary spiral.

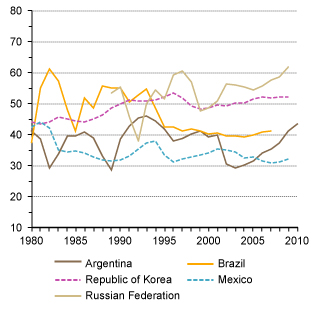

In most developing and transition economies, the share of wages has behaved differently for the period as a whole. That share is generally between 35 and 50 per cent of GDP – compared with approximately 60 per cent of GDP in developed economies – and it tends to oscillate significantly, owing mainly to sudden changes in real wages. In many of these economies, the share of wages in national income tended to fall between the 1980s and early 2000s, but has started to recover since the mid-2000s, though it has not yet reached the levels of the 1990s (Chart) Share of wages in national income in selected developing and transition economies, 1980-2010

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Chart 1.5), based on OECD, Main Economic Indicators database; and Lindenboim, Kennedy and Graña, 2011 . The positive evolution of wages and the role played by incomes policies, particularly transfer programmes to the poor, have been significant factors behind the present “two-speed recovery”.

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Chart 1.5), based on OECD, Main Economic Indicators database; and Lindenboim, Kennedy and Graña, 2011 . The positive evolution of wages and the role played by incomes policies, particularly transfer programmes to the poor, have been significant factors behind the present “two-speed recovery”.

In developed countries, real wages grew on average at less than 1 per cent per annum before the crisis, which is below the rate of productivity gains; they then declined during the crisis, and tended to recover very slowly in 2010. Arguably, the early move to a more contractionary fiscal policy and the relatively high levels of idle capacity and unemployment imply that the pressures for higher wages could remain subdued, thereby reducing the chances of a wages-led recovery.

In contrast, since the mid-2000s, in all developing regions and in CISCommonwealth of Independent States,real wages have been growing, in some instances quite rapidly (Table)  . In some countries, this may represent a recovery from the steep reductions in the 1990s or early 2000s, and in others it is more than a mere recovery, as wages follow the same path as productivity gains. Even during the difficult years of 2008 and 2009, real wages did not fall in most developing countries, as had generally been the case in previous economic crises. This suggests that to some extent, recovery in developing countries was driven by an increase in domestic demand and that real wage growth has been an integral part of the economic revival.

. In some countries, this may represent a recovery from the steep reductions in the 1990s or early 2000s, and in others it is more than a mere recovery, as wages follow the same path as productivity gains. Even during the difficult years of 2008 and 2009, real wages did not fall in most developing countries, as had generally been the case in previous economic crises. This suggests that to some extent, recovery in developing countries was driven by an increase in domestic demand and that real wage growth has been an integral part of the economic revival.

Further, incomes policy could also be used to complement more expansionary fiscal policy in order to control prices, allowing for a more robust recovery with relatively stable prices. Subsidies to reduce the costs of basic consumption baskets for the lower income groups, which have a higher propensity to spend, and direct transfers to the less privileged in society might provide an alternative source of demand growth, helping create jobs and leading to a self-sustaining recovery.

Highlights

- There is little scope for monetary policy to provide additional stimulus, and higher public-debt-to-GDP ratios have convinced many governments that they should shift to fiscal tightening;

- Other policy tools, such as incomes policy, could play a strategic role in dealing with the present challenges;

- Wage shares have declined slowly, but steadily over the past 30 years, in particular in developed countries;

- In developing countries, wage shares tended to fall between the 1980s and early 2000s, but have started to recover since the mid-2000s;

- The positive evolution of wages and the role played by incomes policies in developing countries, in contrast with developed countries, are among the main factors behind the present “two-speed recovery”.

To learn more

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2011, Chapter I Current Trends and Issues in the World Economy, UNCTAD/TDR/2011

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2010, Chapter III, Macroeconomic Aspects of Job Creation and Unemployment, UNCTAD/TDR/2010

UNCTAD contribution to the G20 Framework Working Group: Incomes Policies as Tools to Promote Strong, Sustainable and Balanced Growth, September 2011

Social Unrest Paves the Way: A Fresh Start for Economic Growth with Social Equity, UNCTAD Policy Briefs, No. 21, 21/02/2011