Monetary policy and interest rates

Monetary policy and interest rates

From the mid-1940s to the early 1970s, low interest rates Interest rate is the cost or price of borrowing, or the gain from lending, normally expressed as an annual percentage amount.

favoured fiscal expansion for recovery and for the creation of the Welfare State in developed countries, as well as for infrastructure building and sustained growth rates in the developing world. This period is often referred to as the Golden Age of Capitalism. The evolution of interest rates dynamics saw two important breaks. In the first break, starting in the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was a sharp increase in interest rates, when inflationary pressures led to a shift in monetary policy priorities from full employment to price stability. The second break, which took place in the early 2000s, relates to the lower rates of interest, on average, in developed countries, after the collapse the dot-com financial bubble.

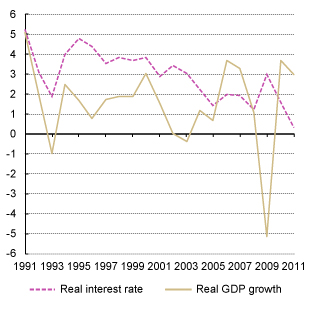

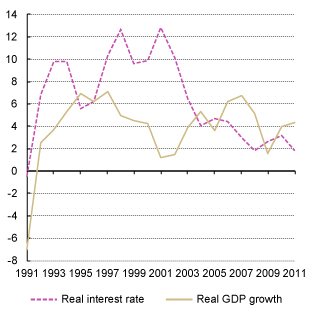

Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of Germany, 1991-2011

(Percentage)

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012

After the first break, for the most part real interest rates Real interest rate is nominal interest rate compensated for inflation.

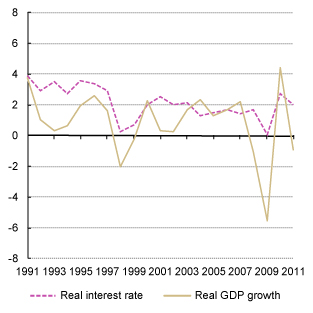

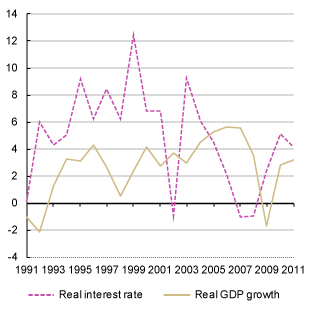

were higher than the rate of GDP gross domestic product growth in developed countries (e.g. Germany, Japan (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of Japan, 1991-2011

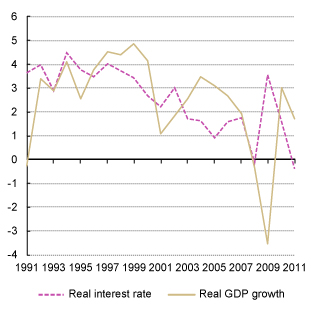

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 and the United States (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of the United States, 1991-2011

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 and the United States (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of the United States, 1991-2011

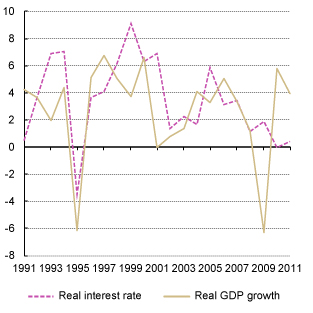

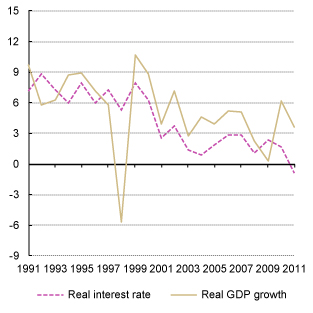

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 ), as well as in Latin America (e.g. Mexico (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of Mexico, 1991-2011

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 ), as well as in Latin America (e.g. Mexico (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of Mexico, 1991-2011

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 , in Eastern Europe (e.g. Poland (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of Poland, 1991-2011

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 , in Eastern Europe (e.g. Poland (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of Poland, 1991-2011

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 ), and in sub-Saharan Africa (e.g. South Africa (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of South Africa, 1991-2011

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 ), and in sub-Saharan Africa (e.g. South Africa (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of South Africa, 1991-2011

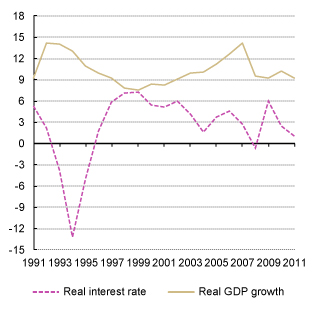

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 ), but not in the Asian developing economies (e.g. China (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of China, 1991-2011

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 ), but not in the Asian developing economies (e.g. China (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of China, 1991-2011

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 and the Republic of Korea (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of the Republic of Korea, 1991-2011

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 and the Republic of Korea (Chart) Real interest rate and real gross domestic product growth of the Republic of Korea, 1991-2011

(Percentage)  Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 ). In the subsequent phase, at least between 2001 and 2003 and the Great Recession, there was a reversal, with real interest rates lower than growth rates in almost all countries. And despite the brief fall in GDP, this trend has continued to the present day.

Source: UNCTAD, TDR 2011 (Table 1.1 and chart 3.3), updated March 2012 ). In the subsequent phase, at least between 2001 and 2003 and the Great Recession, there was a reversal, with real interest rates lower than growth rates in almost all countries. And despite the brief fall in GDP, this trend has continued to the present day.

This is an important result, since low interest rates moderate the growth of debt, while the rate of growth of GDP, which goes hand in hand with government revenue and family income, is a measure of the ability to repay debt. Hence, when the rate of interest is below the rate of growth of the economy, the amount of debt accumulated can normally be paid, and the economy is on a sustainable path.

Quantitative easing, a situation in which the central bank buys long-term government bonds, rather than just short-term bills, in order to maintain long-term interest rates relatively low, has been particularly important in the United States. This contrasts with the limitations of the European Central Bank in buying government bonds from member countries, which has implied that interest rates on government bonds of peripheral European Union countries have risen considerably during a very difficult economic situation. Although maintaining low interest rates on the public debt is important for avoiding a further deterioration of public finances, it will not restart credit provision to the private sector, as long as de-leveraging is not achieved. Monetary expansion could promote economic growth more effectively if it were linked to the generation of higher domestic demand or to the restructuring of mortgage debts.

The reduction of interest rates after the crisis, and quantitative easing where pursued, has been an essential instrument to preclude a major crisis of the same proportion of the Great Depression, but insufficient to promote a full fledged recovery. For that additional support from fiscal and income policies is still needed.

Highlights

- When the rate of interest is below the rate of growth of an economy, the amount of debt accumulated can normally be paid, and the economy is on a sustainable path;

- Between 2001 and 2007, real interest rates have been lower than growth rates in almost all countries. This trend has continued from 2010 onwards;

- The reduction of interest rates after the crisis has been an essential instrument to preclude an even bigger crisis, but insufficient to promote a fully fledged recovery;

- Quantitative easing, and other unconventional monetary policy measures used to maintain interest rates relatively low and expand credit, should be used to support the recovery;

- Additional fiscal stimulus and income policies are also needed in order to promote a fully fledged recovery.

To learn more

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2011, Chapter I Current Trends and Issues in the World Economy, UNCTAD/TDR/2011

UNCTAD Trade and Development Report 2011, Chapter III Fiscal Space, Debt Sustainability and Economic Growth, UNCTAD/TDR/2011

The crisis of a Century, UNCTAD Policy Briefs, No. 3, 06/10/2008